This is the 2nd installation of Phil’s trip diary. Catch up now:

Read Part 1 | Read Part 3 | Read Part 4

Go learn more about our Bolivia Road of Death Adventure

Tuesday November 8th — La Higuera

We assembled at ten in the morning in front of the hotel and walked down to the main square. Cory had arranged a guide to take us to the memorial of Che Guevara. This was the place they brought his body to put on display for the world to see after he was executed. The memorial was located a little ways out of town. It was a brand new structure, and had photographic displays and history of Che, his life, his accomplishments and his last campaign in the mountains of Bolivia. The guide then led us down to a monument building where his body and several of his comrades had been buried in secret, and had laid there, undiscovered, for 28 years. This area used to be the old military airport. Now it served as a small municipal airport. The guide himself had come to see the bodies when he was a young man, all intertwined together, left and forgotten, buried in the ground.

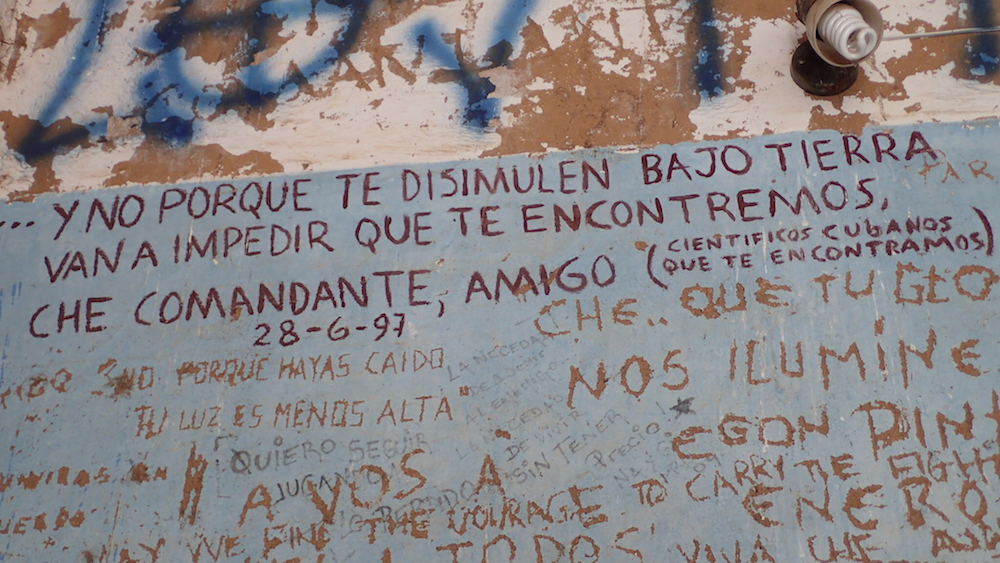

From there, we were brought by taxi to the still functioning hospital, where the old laundry, in its original form, still stood. The walls and wash basins were covered with graffiti by fans and well wishers of the Che. You might recognize it from the iconic picture of him lying there, eyes open, head propped up. We stood to hear the explanation of how the Bolivian government showed his body to the press and the public, to prove that indeed the great Che Guevara was dead. It is a suddenly powerful moment any time you stand in the very spot of a famous historical event. The force of it was palpable.

One message written on the wall by the ones that had searched and found his hidden body struck the chord of the moment: written in large letters high on the wall: “just because they buried you away, does not mean you were forgotten.” This little town, on the eastern slopes of the Andes, was witness to death of the most iconic communist revolutionary the world had ever seen. He now rested in the minds and hearts of those townspeople as a saint.

What was most touching about all of this history, was that we were the only tourists in that entire town and that this original building had no lines of people, no ticket office. We had just walked through a collection of functioning hospital buildings with rooms full of actual patients and staff. It was for our group only to take in this historical scene.

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped into a hole in the wall restaurant and ate a couple of Saltenas for lunch. These pastries were much like empanadas, filled with chicken, beef, onions spices and olives. A simple lunch that the locals enjoy throughout Bolivia.

We were on the bikes by 1:30PM with only 21 miles as the crow flies to our destination. The small village of La Higuera was the place where the Bolivian government had captured and killed Che. The road into La Higuera was steep, precipitous dirt road that wound around the mountains. It took us over two hours to make the journey to our destination.

Along the way, we stopped in a small hill town, where, in the main plaza a party was in full swing complete with live music, dancing and drinking. Half the town was drunk and vivacious.

A little further along the road, we came to a collection of buildings nestled in the thick forest. We had arrived in La Higuera. Our accommodation for the night was the old Telegraph office that Che had used to communicate to Cuba. His messages from this very place were the ones that were intercepted by the Bolivian military, giving away his position.

The quaint pension was one of those places that suddenly put you into a dreamlike state. A small open-aired courtyard with a collection of tables and chairs, surrounded by tall Eucalyptus trees and thick bush gave it the feel of an oasis. Cows, pigs, dogs and roosters could be heard all around us. The main street through the village had little traffic. Just one car came by during the entire evening.

We walked up into the main center of the village to the school where Che was taken, bound, and killed. There were just a couple of buildings, and few people in sight. Again, there we were, the only tourists to take in the is historic place.

Our visit was cut short by a sudden downpour, the likes the town had not seen for six months. Lightning streaked across the sky while torrents of rain chucked it down. It was over as fast as it had started and as the clouds parted, the last remaining rays of the setting sun seemed to say ” The show is now over.” There is nothing like a spectacular natural display!

That night we crowded into the small building that used to be the original telegraph building. By candle light we enjoyed a delicious meal of potatoes, salad and pork. Afterwards, we were served chocolate pudding (with coconut sprinkles) and an aperitif: made from coca leaves. So satisfying and welcoming was the atmosphere of this modest pension, that many of the riders asked if we could stay longer than just one night!

The eventful day ended around a campfire, where Juan, the owner, passed around the local drink and told us about the capture of Che and little known facts about what really went on. He was drawn to this place because of its history, and had spent 14 years here, learning all he could about that fateful day.

Funny, it was election day back home and most of America sat glued to a TV. And there we were, circled around a fire, far removed from cell service, electricity and mainstream. As the fire died I walked a lonely trail through the bush to my room. Fireflies danced amongst the tree branches and crickets triumphantly played their tune.

Wednesday, November 9th — La Higuera

After breakfast we walked up to the old schoolhouse of the village. Along the way, there were few houses, dogs lying in the dirt, cow patties, a new school and a sparkling statue of Che. The “town center” was just a collection of humble buildings, some being used, some not. The actual schoolhouse was a one-room affair adorned with memorabilia of Che and gifts from well wishers. The lady who let us in explained that the one room used to be divided into two small sections and she pointed at a chair that was against the wall. This, she said, was the very chair that Che sat in when he was executed.

He had been brought to this school by the Bolivian army. They awaited orders. A helicopter landed and out came a CIA agent. There are various versions of this story, but the one that our guide had told in Valle Grande went that the President of Bolivia was reluctant to give Che over to the USA. He also did not want to make the mistake of letting Che escape, since Mexico had made the mistake of letting Fidel and his brother live and they gone on to orchestrate a successful revolution in Cuba. So, the order was given to kill him. One soldier volunteered, and in order to do the deed, made himself drunk in order not to feel remorse. In that small schoolhouse far away in the countryside of Bolivia, where the children of the village were still coming to school that day, that soldier shot Che several times until he was dead.

We were the only tourists in that village and were the only ones that morning to experience that historical place. As we geared up to leave and received waves from the locals and weaved in and out of cows on the road, the ghost of that moment, its effect around the world and the legacy it had left followed us throughout the day.

We spent another 100 miles riding through the mountains on dirt roads, gaining and losing thousands of feet elevation. All around us were broad vistas of mountains in all directions complete with small farm plots dotting the landscape. Traffic was rare. We were taking the back route to Sucre and it was purely magnificent. I had ridden the famed Copper Canyon in Mexico, and this was everything and more, in terms of vegetation, elevation change, and rugged road.

We worked our way down to the bottom of a river valley. Cactus and dry scrub brush dominated the landscape. A river of chocolate rushed below us and alongside us as we worked our way along it, down the valley. The temperature sky rocketed. We had gone from 9,000 feet to 3,000 feet in a matter of minutes.

There were few houses – more abandoned ones than used ones. We passed cars sparingly. There were large deposits of black rock all around, which gave the area a “land of the lost” effect. Mountains towered far above.

We pulled into a small town, dusted off and plopped down in a local restaurant. The menu was simple: all you had to do was order the “plato del dia” or the “daily meal”. It was comprised of a basic soup with a chunk of fat beef in it and a main dish of grilled chicken, yucca, potatoes, and a salad of corn, mayonnaise, and onion. All of this was at the very reasonable price of a dollar and a half.

Outside of the restaurant, curious children had gathered as the motorcycles were all lined up and made quite a presence in this small, cobblestone town. The locals for the most part were very respectful of us and maintained their distance with inquisitive looks, but never juxtaposed themselves amongst our bikes and the group. They just went on with business as usual. It was very refreshing, as it lent to a feeling of acceptance.

Soon after, we arrived at a last town, where the pavement would begin for the last easy blast into the UNESCO World Heritage city of Sucre. It would have been a relatively easy day if it were not for the element of adventure which snuck up on us.

I was the sweep rider and as I entered this town, Mike was off to the side of the road with a flat rear tire. I urged him to ride one more block to get into the shade of a building in the town, instead of fixing the flat in the blaring sun. Once positioned there, I road ahead to alert the group. Ian and Howard decided to double back and help. We fixed the flat without incident and as we collected our gear to leave, Ian noticed Howard’s rear tire was hissing. That was two flats in a matter on one meter! I called Cory and told him about this and he told me that the support truck has run into a problem and would not come along for another 3 to 4 hours. So, we rolled up our sleeved and attempted to repair Mike’s old tube, which had taken a nail.

The problem was that the nail had punctured the tube in several places when he rode on the flat. We did not know this, and so we went through a procession of putting the tire on and taking it off trying to locate the reason it would not inflate fully. We decided to put a front tire tube in the back and see if that would hold to Sucre. So, after 2 hours of tire changing practice, we geared up to leave only to see that my front tire was half flat. That makes it THREE flats in three meters distance! Since it was only half flat, I decided to fill it up fully with air and see how far it would go. We were out of replacement tubes, the sun was starting to go down, and we had 70 miles to go. The rest of the group had already moved on to Sucre, so we were on our own, or at least until the support truck caught up.

On the pavement we made it 30 km to a gas station, filled up, and as we clipped along, I suddenly realized the riders behind me were not there. Upon doubling back, I started to get a wobble in the front tire and sure enough the hole was getting bigger in the tube and I had to inflate it twice in a matter of miles just to make it back to them. And there they were, strung along the side of the road, with another flat! So many flats in such a small space of time, and the sun went down and there we were in the dark along the road somewhere in Bolivia.

After a while, the support truck finally came to our rescue and it was just a matter of downloading the spare bike to get us on our way.

We spent the rest of the ride clipping along is complete darkness, and as the temperature plummeted and we climbed higher into the Andes, fatigue started to set in. We finally entered the city of Sucre and were relieved to finally park the bikes and get checked in to the hotel.

We walked to a local restaurant and our group of four, joined by the two support truck guys, relived our days’ adventures around the dinner table.

Thursday, November 10th — Sucre

The city of Sucre was founded by Simon Bolivar the great liberator of South America, who led the pan South American revolution against the Spanish crown. Founded around 1560, this city is widely regarded as the most elegant in Bolivia. We had a free day to explore, and each rider came back with a tale to tell, whether they were shopping, museum hunting, or just wandering the local markets.

I can’t help going to the central plaza to just people watch, and it was the perfect cathartic activity after such a long day. Pigeons, demonstrations, street venders and friends united to frame in the park scene. The streets were narrow and usually one way in the city. Buses belched thick acrid smoke, zebra-clad municipal workers helped tourists on every street corner.

If you ever go to Sucre, make sure to go to the public market. It was a sensory smorgasbord. Each section was tightly organized: eggs, cheese, meat, flowers, vegetables…it went on and on. Absolutely no foreigners were to be seen – this was a daily living and breathing market!

We all collected at the end of the day and each rider had a story to tell. Our hotel featured a third floor terrace overlooking the city and it was one of those classic times when traveling that the sun sets over a white-washed city, leaving the colors do their magic. You reunite with your fellow travelers and tell stories of the day.

That night Cory picked out a fantastic French restaurant and we dined on perfectly cooked steak and Bolivian Malbec wine.

Sucre had something going with it all. It was a vibrant, inviting city. Every interaction I had with the locals was sincere and friendly. It was a delight to explore its streets, parks and back alleyways. It was a place, I suppose, I could easily spend more time in, perhaps years. I highly recommend anyone to come to this humble and beautiful place.

Read Part 1 | Read Part 3 | Read Part 4